by Angie Jaillet-Wentling

The best part of understanding history isn’t memorizing dates, places, or facts. It’s about how you can inspire engagement, curiosity, and even unlock the capacity to do big things in little ways, sometimes just by trying to make your way in a world not terribly predisposed to help you do it. Looking back to move forward helps us know that we can be ordinary but still capable of the extraordinary. We can set the foundation stones that others can build upon. We can rely on the strong roots of forestry’s forbears to provide the minerals, water, and nutrients needed to support new growth in young professionals.

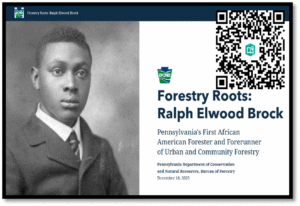

All his accomplishments aside, one of Ralph Brock’s lasting legacies

is how he inspires the future in the present.

Researching Ralph Brock’s story to develop PA DCNR’s latest Untold Stories effort, a Story Map featuring a tour of Ralph’s life (found here: https://arcg.is/1Dv4PP1) and the impact he had as a young Pennsylvania forester, and later as a forerunner to urban forestry, reminded me just how much Ralph Brock’s story could mean to younger generations seeking a space to see themselves in our forests.

People need to be able to imagine themselves in new environments and feel a sense of belonging, for instance, in forests and wild spaces or professions in which they’ve been traditionally underrepresented. That doesn’t mean we rewrite history to accommodate that, but it does mean that we can keep asking questions of history. What is written can be wrong, misunderstood, or even just missing too many pieces of the puzzle to accurately understand. Asking questions won’t always mean finding the answer you seek; it might show what deviates from what you thought you knew. One question we asked was why Ralph left employment in the Pennsylvania state forest system in 1911.

At the time, newspapers ran notice of his departure detailing the high quality and breadth of his work. Other sources also support that he left with every reason to be proud of his work at the Mont Alto nursery. Unfortunately, according to multiple contemporary sources (including a former classmate and George Wirt), the reason he left was because when racial tensions arose in the nursery fields, Ralph’s leaders failed to provide a workable solution. Instead of addressing the instigators, Ralph was asked to leave a position that he had worked so hard to develop. It was easier to upend his fruitful career than it was to affect change, but it didn’t derail it for long. He found other forestry work helping to create and maintain the gardens and courtyards around which Rockefeller built architecturally significant apartment complexes that provided affordable housing for a rising African American middle class in the 1920s and 1930s. He helped bring green spaces and urban forests to New York and opportunities to other young families, like his own. Today, he provides inspiration to young professionals, like those in my crews, who see in his story that they have roots in what we do; that despite challenges, they can persist, prosper, and help others too.