Scattered remnants of a diminishing boreal forest are the last footholds for the state-endangered northern flying squirrel in northeastern Pennsylvania. The diminutive nocturnal rodent, with its disproportionately large eyes and unique ability to glide through the air, is in trouble. Forest fragmentation, the loss of trees necessary for food and shelter, and competition with a close cousin have kept this species precariously clinging to survival in the commonwealth. But help may be on the way in the form of a habitat-improvement project taking shape on state game lands in the Poconos.

Similar but Different

Pennsylvania is home to two species of flying squirrels. Both weigh less than 3 ounces, are 8 to 10 inches long including the tail, and appear identical. The southern flying squirrel (SFS) and northern flying squirrel (NFS) are brown on the back – the northern sporting a slightly reddish tint. The key differentiating physical characteristic is the SFS has belly hairs that are all white, while the NFS has belly hairs that are whitish at the tip, but grayish at the base.

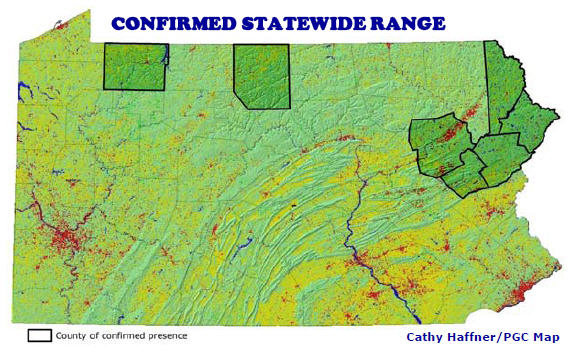

The SFS is a habitat generalist found in hardwood forests throughout the state where it eats a steady diet of nuts, seeds, and insects. In contrast, the NFS is a habitat specialist that requires unbroken stands of coniferous forests for survival. An ongoing study in Pennsylvania initiated in 2001 found the NFS only in the Pocono region and at isolated sites in Warren and Potter counties. While the NFS’s diet is somewhat varied, it is partial to consuming lichens and underground fungi found in hemlock/spruce forests. The specific habitat requirements of the NFS made this species especially vulnerable to population declines.

Night Gliders

Northern flying squirrels are most active during the evening hours and their large eyes are an adaptation for nocturnal activity. Flying squirrels have skin flaps that extend between the wrists and ankles, and tails that are flattened top to bottom and used for steering when gliding from tree to tree. Northern flying squirrels travel principally by gliding (traveling an average distance of 65 feet) and take short jumps while on the ground. Tree cavities provide the best nest sites and one litter of young is produced in mid-to-late May, with an average litter size of two. The young squirrels are fully weaned and ready for “test flights” at about three months. Pennsylvania’s flying squirrels are active year-round and they may cluster together in cold weather to keep warm. Predators include owls, hawks, bobcats, raccoons, and snakes.

Shrinking Habitat

Factors influencing the northern flying squirrels decline in Pennsylvania include:

• Mass clearcutting and wildfires that removed conifer trees, especially eastern hemlock and red spruce, from the landscape in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

• Loss of older conifer stands to development across the NFS range.

• The recent declining health of hemlock forest stands caused by hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA).

• Competition with the SFS in marginal habitat. Research suggests that the SFS may carry and transmit an intestinal parasite lethal to the NFS.

The NFS-Fungus Connection

The primary food source of the NFS is the fruiting body (truffle) of an underground fungus that grows on the roots of conifer trees. Hemlock and spruce trees depend on the fungi for efficient water uptake and the fungi rely on their tree hosts as a source of carbohydrates. Maintaining this three-component beneficial relationship was a key consideration when Game Commission foresters and biologists developed a plan to improve habitat conditions for the NFS.

State Game Lands 149

State Game Lands (SGL) 149 encompasses approximately 1,991 acres within the Pocono Plateau region in Foster Township, Luzerne County. The game lands has documented populations of NFS along the hemlock-dominated Sandy Run stream corridor and adjoining uplands that provide the habitat necessary for this species to exist.

The SGL 149 Management Plan identified the need to maintain and expand the game lands’ existing boreal forest component to support NFS populations. In 2011, Northeast Region foresters, mammal biologists, and region biologists delineated existing core NFS habitat along Sandy Run. A 300-foot buffer zone was then designated around the core habitat to meet NFS foraging needs, bringing the total project area to 650 acres.

The Ideal Tree

While red spruce is scattered throughout SGL 149, it is not present in great numbers or found forming established stands. Red spruce can act as a surrogate tree species for birds and mammals that depend on eastern hemlock. Red spruce is immune to HWA and is shade tolerant. Seedlings planted under a hemlock understory can persist over 40 years, awaiting to be released with additional amounts of sunlight. When Game Commission biologists conduct NFS studies, most of the squirrels are captured within 50 feet of a red spruce. The continuing destruction of Pennsylvania’s hemlocks caused by HWA made this tree the perfect choice to plant and improve NFS habitat.

Planting with a Purpose

Planting red spruce trees to improve NFS habitat on SGL 149 was initiated by Game Commission personnel before the ravages of HWA affected hemlock stands along Sandy Run. But the anticipated spread of the disease to this game lands was at the forefront of habitat-improvement planning. Red spruce seedlings were raised at the Game Commission’s Howard Nursery from seed-producing cones collected at isolated stand locations in northeastern Pennsylvania. Over 2,000 bare-root trees were introduced into the soil by agency foresters, biologists, and habitat-improvement personnel in the spring of 2011. Many were planted directly under the core NFS habitat hemlock canopy. Foresters reasoned that the inevitable thinning of the hemlock branches would result in increased sunlight reaching the red spruce seedlings below – and allow them to reach for the sky. Other seedlings were planted in canopy gaps within the surrounding buffer zone with the hopes of extending the core area along Sandy Run to nearby conifer stands.

The Present

Game Commission Northeast Region forester Zach Wismer recently made a site visit to evaluate the project area. He discovered that seedlings from the 2011 plantings are well established and persisting in areas with full conifer shade – although they show no noticeable growth.

“This speaks to their extreme shade tolerance and low palatability to white-tailed deer,” said Wismer. As predicted, HWA is now present in the Sandy Run drainage and affecting mature hemlock in the core NFS habitat. Thinning of hemlock crowns is beginning and the increased sunlight will soon facilitate spruce tree growth. Most seedlings planted in canopy gaps receiving partial sunlight have grown to over 3 feet and they may indeed help realize the goal of extending NFS habitat to nearby conifer stands. Similar NFS habitat improvement projects were initiated by the Game Commission on state game lands in Carbon and Monroe counties in 2012.

Where Are They?

Game Commission biologists gather information on NFS populations while providing squirrels with a place for raising their young by installing and monitoring nesting boxes in and around known NFS habitat. These artificial tree cavities decrease the risk of predation and increase juvenile survival rate. A network of over 750 boxes are in place at historic and potential NFS sites. Through the use of nesting boxes, biologists have verified new populations and confirmed several more historic ones.

The Future

“The rare Northern flying squirrel is a fascinating member of Pennsylvania’s wildlife community that is rarely observed in a natural state,” said Wismer. “We are working hard to keep it thriving here in Pennsylvania.” This living relic of the northern forests may have been given the opportunity to continue gliding in our woodlands through the dedicated work of Game Commission personnel who looked to the future – and planted a few thousand trees.