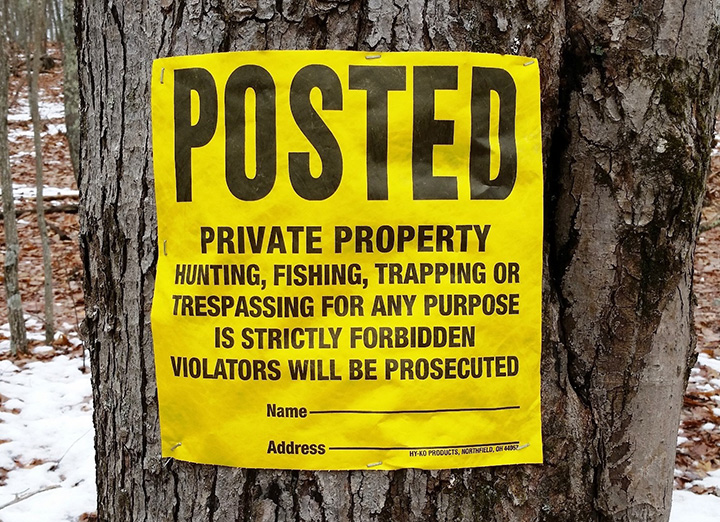

It’s hard to call anyone in a township of 34 a trespasser—that just wouldn’t be polite. Folks in rural Pottersdale took the freedom to roam in forests and streams for granted. So did the people of neighboring communities — that is until the “No Trespassing” signs began to appear.

“More and more private properties around here are being posted each year,” said Ray Savel, a Pottersdale native. “Up here in the mountains, we’re not used to that. People that have lived here all their lives and they can’t use the land.”

When businessman Robert Kelley died and left his family’s 4,400-acre Pottersdale estate to his heirs, residents became uneasy with the prospect of the land being closed off to the community.

A History with the Community

Generations of area residents made their living and their recreation on the Kelley property, also known as the New Garden property. The Kelley family leased land to coal mining and timber operations that were major industries here until the 1950s. Small villages were once erected along the rail tracks in what is now deeply wooded property.

Although privately owned, Kelley’s land was open to hunting and recreation. The land is the only river access for communities on the western shore of the West Branch of the Susquehanna where Pottersdale is located. It’s where fathers taught their children how to hunt and where families would picnic along the banks of the river.

Residents have used the Kelley land for generations. When the large mines were still open, tired work horses hauled train cars of coal all week. Then on Sundays, children would line up at the “pony barn” for rides after church.

Old-timers can recall the tired horses that pulled train cars full of Kelley coal all week providing Sunday recreation. After church, children would line up at the “pony barn” for rides.

To Conserve or Not?

Pottersdale, West Keating and the other communities near the Kelley property are ensconced by 700,000 acres of state forest and game lands including Sproul State Forest.

Robert “Butch” Davey worked as Sproul State Forest’s district forester for over two decades. He knows the history and the residents of Pottersdale and West Keating as well as he knows the Kelley property. When a lawyer from Lock Haven told him that the Kelley estate was for sale, he knew the land should be conserved.

“This is something that the Commonwealth ought to purchase. It has 3,000 feet of frontage on the West Branch of the Susquehanna,” Davey said. “But the Commonwealth doesn’t always have the money at the time a property comes up for sale.”

Davey started making calls. Soon a partnership was forged to pursue the possible conservation of the land. Two private nonprofit organizations, the Northcentral Pennsylvania Conservancy and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, joined with the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry and the Pennsylvania Game Commission.

The Northcentral Pennsylvania Conservancy was willing to buy and hold the land until the state agencies could secure the money to repurchase it for state forest and game land. However, first the Conservancy wanted to know how the community felt about potential state ownership of the land.

The Conservancy held three well-attended public meetings, said Renee Carey, executive director of the Conservancy.

“The people were very concerned about the future of their home,” she said. “Their questions were sharp and plentiful. Their main concern was, once in state hands, what kind of restrictions would be put on their use. Traditionally it was an area where people go hunting and picnicking. We talked about it at every meeting. With their questions answered, the support was overwhelming.”

With the communities in favor of the project, the Northcentral Pennsylvania Conservancy and Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation set out to make it happen.

Making it Happen

The Conservancy and the Elk Foundation embarked on the tricky business of negotiating a land purchase satisfactory to all of the Kelley heirs. They also had to find a lot of money.

They succeeded on both counts. A deal was struck with the heirs. Major contributions were secured from the R. K. Mellon Foundation, the National Wild Turkey Federation, The Great Outdoors Conservancy and the Roy A. Hunt Foundation, as well as many sportsmen’s groups and hundreds of individuals. The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources helped with a $350,000 land trust grant from the Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund.

The land was purchased by the two organizations in 1998. They paid off the back taxes, cleaned the property up and took other steps to ready it for the state. A couple of years later, when the state agencies were ready, they sold it at a loss to them. The Bureau of Forestry established 1,110 acres of new state forest with public access to the river. The Game Commission created 3,330 acres of new elk habitat and hunting grounds.

“They couldn’t have done it without us and we couldn’t have done it without them,” summed up Thom Woodruff, the national lands program manager for the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation.

“I’m really happy about it,” said Savel, the Pottersdale native. “I’m glad it is public. We were worried that people with big money would buy it and post it.”

Elk in Pennsylvania

By the time the Pennsylvania Game Commission was created in 1895, it was too late to save the state’s native elk; the last of the hulking beasts had been killed off 20 years earlier.

The Commission began an effort to recreate an elk herd in 1913 with the importation of Rocky Mountain elk. However, reestablishing the elk proved difficult. Only in the past decade has a healthy population arisen with roughly 800 elk roaming Northcentral Pennsylvania today.

“The Kelley property is important to elk and other wildlife because it bridges the gap between large chunks of public lands,” said Jon DeBerti, wildlife biologist with the Game Commission. DeBerti explained that the elk need large expanses of public land to keep them from getting in trouble with farmers and other private landowners.

“There’s a lot of private land out there. A lot of times, we can’t control what goes on in private land. Everything is so broken up and the Kelley property makes a nice travel way for wildlife between Sproul State Forest and state game lands.”

Elk were released on the Kelley property following the state’s purchase of the land. The Game Commission backfilled old coal seams and planted grasses. Tender shoots of timothy and clover poke from the dark skin of waste coal piles. The sweet plants lure elk, keeping the appetites of the beasts satiated enough to keep them from munching farmers’ crops.

The herd was healthy enough for the Game Commission to hold the first elk hunt in 70 years in 2001.

Thirty licenses were drawn by lottery that first season and 70 in 2002. About 55,000 hunters paid $10 for a chance that first season. All of the proceeds from the license application fee are used for wildlife habitat.

The lottery for Elk licenses takes place in public. Sixty-five-year old Pottersdale native Ray Savel attended the lotteries. This would be the chance in his lifetime to hunt elk near his home. He was one of many whose name wasn’t drawn.

“A few people from Clearfield County, one guy from out west and four kids won themselves a junior bull license,” he reported.

His advice to the four youngsters: “Take me along.”

Location

Pottersdale (Clearfield County)