by guest columnist Tatiana Paden, Executive Office and Archives Coordinator, Chestnut Hill Conservancy.

by guest columnist Tatiana Paden, Executive Office and Archives Coordinator, Chestnut Hill Conservancy.

Representation is essential in adequately recording history, especially today–both big and small milestones. The Black community of Philadelphia has a rich history, and Chestnut Hill is a part of that. My name is Tatiana Paden. I’m the Executive Office and Archives Coordinator for Chestnut Hill Conservancy. While working in the Archives, I have learned so much about the great history of Chestnut Hill. The Conservancy’s archive is a vast collection of amazing stories and pictures. After graduating from Temple with my degree in Historic Preservation, I knew I wanted to focus more on preserving the history of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. While there is representation from the Black community in the collection, our goal is to collect even more. I have chosen a few stories from our Archives to give some of the great examples the Conservancy has in hopes of getting more people involved in preserving and sharing their local Black history.

Credit: Chestnut Hill Conservancy | Caption: Fred Howard and Margie Pointer were the first Black students bussed to Jenks from other city areas. This is a 1952 photo of their 8th-grade class.

In 1945, a young boy by the name of Fred A. Howard was bussed in from Germantown to become the first Black student in his class at Jenks School. Very few Black children were living in Chestnut Hill and attending Jenks School before this bussing initiative. Then in 1952, when he was in the 8th grade, another Black student Margie Pointer joined him. They would both flourish and graduate from Jenks. Thanks to this photograph, we are reminded of this legacy. This bus integration initiative by Jenks started a chain reaction in the area.

In 1954 Springside School, an all girls private school in Chestnut Hill, enacted a similar program. An anonymous grant of $100,000 was given to the school to “Find and bring in worthy Black students,” said Previous Superintendent Eleanor Potter in an interview with David Contosta, Professor at Chestnut Hill College, friend and Collections Committee member of the Conservancy. Springside chose two sisters to attend. They excelled and graduated from Springside with Honors. Thanks to her oral history interview, this milestone was documented to be remembered. One of my favorite quotes is by Raghu Rai, “A photograph has picked up a fact of life, and that fact will live forever.” Today more than ever, we see the importance of photos and documentation, not just in the bad times but in the good. Having a definitive way of making your mark in history can simply be through a picture.

Credit: Chestnut Hill Conservancy | Caption: The Rev. Jesse Jackson, recruiting Chestnut Hill College students for his Rainbow Registration Crusade, 1992.

Jesse Jackson has been a pillar in the civil rights movement since its inception. From starting Operation Bread Basket to joining arms with Dr. King and being by his side until King’s assassination. Rev. Jackson made a vast footprint on America and even helped to make a change here in Chestnut Hill. In 1992, Rev. Jackson came to Chestnut Hill College (CHC) to register more young people to vote. This crusade was spearheaded by his organization, The National Rainbow Coalition. Over 1,000 students came to hear him speak. It was a collaboration between CHC and the United Bank of Philadelphia, the city’s first Black-controlled bank. “Twenty-nine years later, the law is on our side. We have the right to vote,” said Rev. Jackson that day in 1992. Hundreds of CHC students were registered to vote thanks to his efforts. Rev. Jackson got students to understand that your fight starts locally, right where you are. The Black community of this area is no stranger to that fight.

Racial integration in Chestnut Hill became a long-fought battle, growing to its boiling point in the late 1960s. The Pipeline was an integrated community organization founded in 1967 that fought to integrate the North Philadelphian Black Community into Chestnut Hill. The catalyst for the Pipeline was a protest of students who sought the right to equal learning and living opportunities.

After a tense first year, the Pipeline did many acts of community development, like opening up a thrift store in a building they purchased at 1818 Susquehanna Ave. The Pipeline transferred ownership of the building to a Black community leader, keeping the building and store Black-owned. They then used some of the thrift store’s revenue to help a local family on welfare. Later, the Pipeline started talks with the Chestnut Hill Community Association, which created its Human Relations Committee in 1968 in response to the creation of the Pipeline. This Committee discussed topics such as why Chestnut Hill was not integrated yet, stopping the panic that might occur when Black people did begin to move in, and even bringing up the idea of raising money to give reparations to Black residents in the surrounding area.

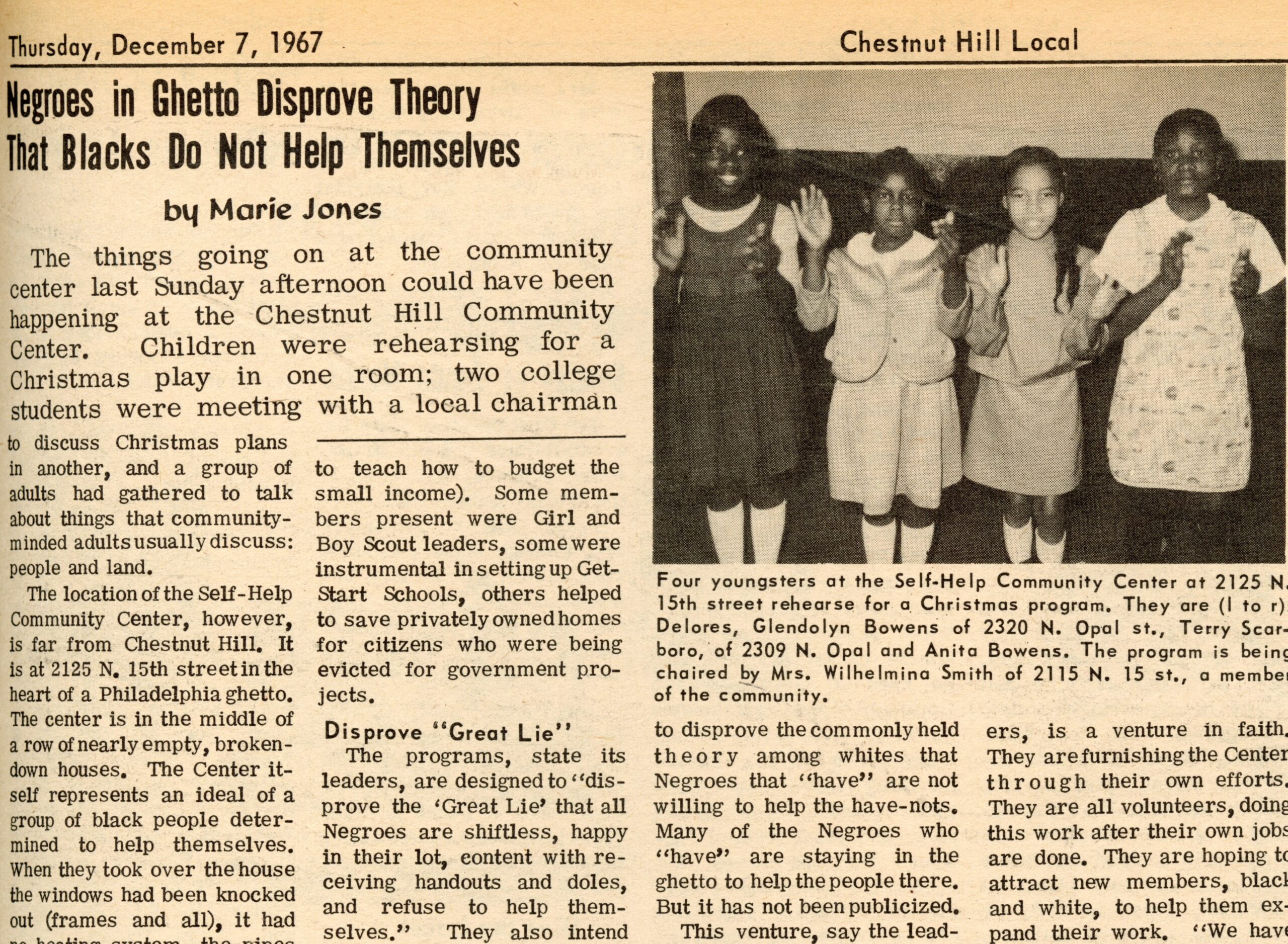

Credit: Chestnut Hill Conservancy | Caption: Chestnut Hill Local Article, Dec 7, 1967, “Negroes in Ghetto Disprove Theory That Blacks Don’t Help Themselves” by Marie Jones.

Through this tense time, the locally affected Black community created the “Self-Help Community Center ” in a rowhouse at 2125 N 15th St. The Black community created the space since they didn’t have access to the Chestnut Hill Community Center at the time. As a result, the row home became a community haven. The Chestnut Hill Local spotlighted this in an article on Dec 7, 1967. Today, the site sits as an empty, vacant lot. However, thanks to the Chestnut Hill Locals’ coverage of this time, and the Conservancy Archives’ Lloyd Wells Collection, this local fight can be remembered and referenced for years. By the 1970s, the dust began to settle, and the Pipeline and other committees began to disperse quietly. But, The Pipeline still conducted many community help efforts through local contributors.

BIPOC history is critical and valuable and deserves to be cataloged as much as anyone else’s. It may seem like a simple family story or photo now, but in 20 to 70 years, it could be a vital piece of historical information. I ask Black people to please cherish your heirlooms. Share and document your family’s stories. Donate to your community’s historical societies and Archives. You may even find a historic local artifact in your attic or basement. The little things are so much more valuable than we realize. When you preserve those pieces with love, you preserve us.

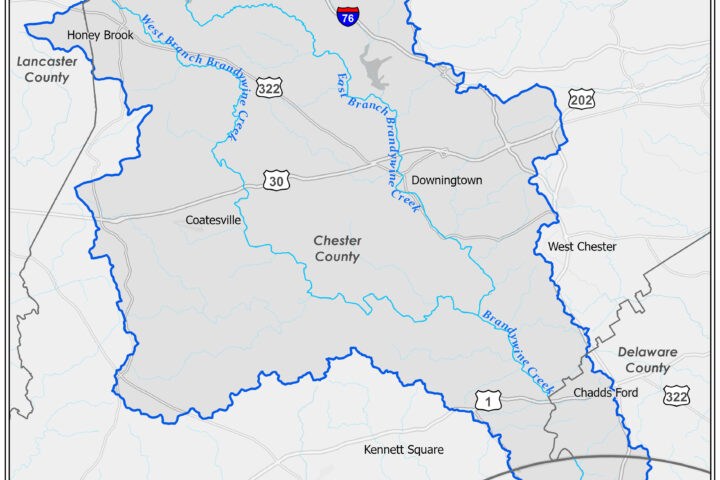

WeConservePA asked Ms. Paden and Chestnut Hill Conservancy if we could republish this piece, acknowledging that histories and stories of the land and people have historically always been critical aspects of conservation and stewardship.