by Jamie Withers and Kirstin Dorshimer

Fossilized Forests

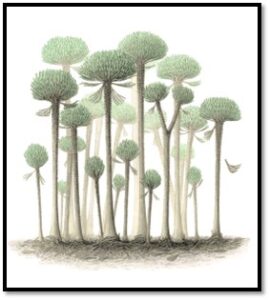

Devonian fossil forest life reconstruction showing Calamophyton. (Picture credit: Peter Giesen/Chris Berry)

You may have heard of the recent discovery of the world’s oldest fossil forest on the southwest coast of England, preserved in 390-million-year-old sandstone from the Devonian Period. Until this time, the oldest known forest was thought to exist 386 million years ago, stretching from New York to Pennsylvania.

The Devonian Period is a pivotal time for Earth, as trees and other plants became established, but little is known about these early forests. England’s ancient forest has now revealed much of the ecology of this type of forest – a semi-arid plain with evidence of small, crisscrossing river channels in a densely packed forest, mainly consisting of Calamophyton trees.

Grasses had yet to develop and establish at this time, so undergrowth was almost non-existent, but there were twigs and debris dropped by the trees as suggested by the fossils preserved in the sediment layers. It appears the vast abundance of debris shed by Calamophyton trees accumulated and affected the way rivers flowed, marking a time when rivers began to behave in a fundamentally different way than before.

Most of Pennsylvania’s ancient forests and early vegetation were preserved as coal during the Carboniferous Period (359 to 299 million years ago). Geographically, Pennsylvania was located near the equator and covered in dense, swampy, tropical forests that flourished all year. In swampy and marshy environments, dead plant materials only partially decomposed due to anoxic conditions, thus minimizing activity of decay-producing organisms. This ultimately resulted in accumulation of altered organic debris.

Because rates of accumulation, subsidence, and water levels were maintained over a long period, a type of sediment called peat was formed – the first stage in the coal-forming process. Cyclic changes in sea level resulted in advancing shorelines that lead to a quick burial of peat by inorganic sediments, thus followed by compression of the peat from the overlain sediment, a further step toward coal formation. The process ends with retreating shorelines allowing forests to again advance and flourish. The repeated process of advancing and retreating shorelines formed coal beds alternating with layers of limestone.

References:

- Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey (1999). The Geology of Pennsylvania (Special Publication 1). Pennsylvania Geological Survey, Pittsburgh Geological Survey.

- Majumdar, Shyamal K., Miller, E.W., (1983). Pennsylvania Coal: Resources, Technology, and Utilization. The Pennsylvania Academy of Science.

- Earth’s earliest forest revealed in Somerset fossils (cam.ac.uk)

- Carnegie Museum of Natural History – One of the Four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh (carnegiemnh.org)

Forest Fridays is an initiative of DCNR, Bureau of Forestry, published weekly.